How one woman broke into a part of design where women were seldom allowed to explore and decided she was there to stay.

She is known as the godmother of Industrial design, and for good reason. Bell Kogan had an extremely prolific career traversing the intersection of product design, art, and graphical thinking. Considered the first female industrial designer in the US (1) he pushed into the world of industrial design during the time when there was a shift towards professionalism (2), and was a trailblazer by allowing minority actors and disadvantaged people (in particular women) to engage in the new immature industry that was manufacturing in the 1950s. Unfortunately, the canon of design tends to gloss over women and Kogan is no exception. She has been maligned by history, and although this small blog can do no major part in addressing that wrong, it can at least be said that students nearly half a century later consider, value and recognise the significance of her work both for its own merit and what it signifies.

This portrait of Kogan in 1955 shows a powerful and focused designer at apex of her craft. She is pictured using tools that no doubt for the time would have been considered objects solely for the hands of men, like slide rules and protractors, to create complex sketches and drawings. The contented and focused smile that sits on her face perhaps demonstrates the ease with which she plays across plays the craft which she is so excellent in.

When Pierre Bourdieu discusses the economy of cultural goods across all cultural practices, the natural progression is that a culture will accept the producers of that work (3). Kogan, while avidly contributing to her epoch of the design canon, wasn’t promoted to the upper echelons of her profession while her male counterparts were.

Belle Kogan

‘[Design] didn’t just happen’

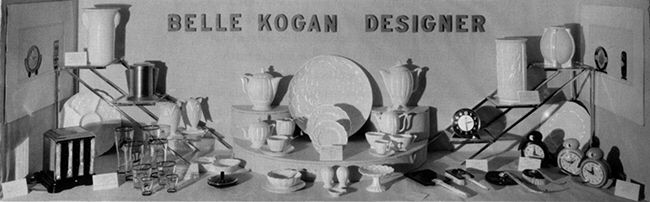

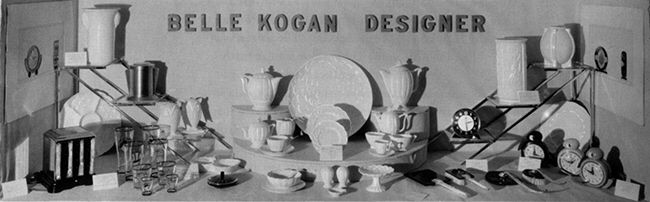

This collection of Kogan’s designs shows the variety of homewares that she created in ceramic, glass, and metal (particularly silver plated brass). These designs with there expertly and seamlessly fit it in to the decorative art that was so prolific and influential in that area.

Her full name clearly posted on the back of this prominent placement signifies a U-turn in recognition for two reasons:

Up until this point, women were consistently undermined as cultural producers in three major ways. Firstly, women systematically faced barriers that prevented them from pursuing design education. For instance, women in the bauhaus were funneled into traditionally feminine disciplines like weaving over male-centric ones like architecture (4). When this barrier is surmounted, the work of female industrial designers was frequently attributed to men. This perpetuated the false narrative that women were incapable of complex design. Otherwise, works frequently went nameless and uncredited. When Kogan began to receive greater recognition, by extension all women may have been recognized as able contributors to the field of industrial design. When a physical good was manufactured and distributed, it in turn became a physical manifestation of women’s design ability.

This gold plated lighter from the final years of the 1930s is one of the most enduring legacies in the history of American Art Deco design. It’s a modified zippo lighter with a simple geometric pattern which complements the clean plane on the surface of the cuboid lighter. What’s curious is that it is easy to imagine a misogynist of the era using such a lighter every day to light cigarettes and cigars in gentleman’s clubs where Kogan was no doubt unable to enter. Such men were likely oblivious that a woman was responsible for this quintessential piece of American manufacturing. Had they known, they may have been less likely to use it as a tool to prop up the patriarchy. It’s this kind of subtle influence and demonstration of complexity in labour that creates a mechanism to transition the misogynist actors of old into the progressives of today. The importance of cultural producers like Kogan, who by virtue of their existence paddle a progressive message, cannot be overstated.

Sweetening the Deal

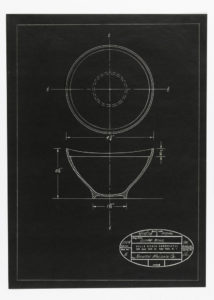

The rendering of the sugar bowl highlights Kogan‘s ability to take elegant and minimal decorative design and sketch workable technical drawings that could be taken straight through to the manufacturing stage. Her ability to run the gamut of the design process was a critical element of Kogen successful design practice (5).

Why we must remember Belle Kogan today

The makeup of current design industries and educational establishments are finally tilting away from the historical hegemony of generally old, white, European men, making now the time to truly acknowledge the creative outputs of disadvantaged groups that have always been poised for recognition.

References:

- https://www.idsa.org/content/belle-kogan-fidsa

- Women designers is there a gender trap?, 1990

- A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste by Pierre Bourdieu, 1984

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-women-bauhaus-school

- https://www.inclusity.com/belle-kogan-1902-2000/