Elizabeth Critchlow is a contemporary designer whom I stumbled upon while researching and attempting to formulate my own opinions on what is good taste in design. She had been profiled and interviewed by Anoushka Khandwala, a contributor to the design magazine Eye on Design (Khandwala 2019). The title “Why Minimalism is a Class Issue + You Might Not Need That Expensive Adobe Subscription” immediately captured my attention (Khandwala 2019). The article and Critchlows ideas on minimalism and class stuck a cord with me. It recalled for me Pierre Bourdieu’s theory on taste from his book “Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste” (Bourdieu 1984, 1-7). Bourdieu believes that taste is learnt (Bourdieu 1984, 1-7). That education and origin dictate a person’s taste rather than viewing “taste in legitimate culture as a gift of nature” (Bourdieu 1984, 7). It is easier to appreciate and enjoy music or art if you are educated in its history and “stylistic properties”, such education is the privilege of those with wealth and high cultural status (Bourdieu 1984, 2-3). In this way he argues peoples preferences and purchases can be a coded message used to indicate their place in society (Bourdieu 1984, 2-3). I consider Bourdieu’s idea that “taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier” an important lens in which to better understand the rise of minimalism as design and as a philosophy (Bourdieu 1984, 6). It is important as a designer that I question the decisions I make in my own design practice and how these relate to different schools of thought. I have grown up surrounded by the accepted idea that minimalism is the supreme aesthetic but Critchlow and Bourdieu have me questioning my prior education. Through looking at my own past work in relation to Critchlows I hope to gain a deeper understanding of why I put such stock in minimalism. This blog post is dedicated to my exploration of the idea that minimalism is simply another style of design not objectively better or worse than any other however its elevation into a lifestyle brand has made the appreciation and use of it a signifier of wealth and social standing.

In today’s day and age the most prevalent style of design is minimalism. Minimalism arose in the 1960s as a rebuff to highly decorated, overtly lavish designs of the past (Cooper 2018). It emphasised the idea “less is more” (Ivanoff 2014). It features a focus on reduced, clean and sleek forms (Schenker 2018). This simplicity however is rarely born out of necessity, materials used in “Minimalists” architecture and interior design are often very expensive and high quality (Fagan 2017). For this reason it is considered the design and look of the upper-class. In much the way that once ravish decoration and excess were used to show once status, today it is once ability to be selective and sleek (Fagan 2017). Minimalism is a modern form of conspicuous consumption. A way to shows ones wealth through purchases. It is a very privileged idea to be able to reject the material. Those who can afford not to clutter their spaces with many cheap possessions. Glass tables that would need to be cleaned after each use to up keep their appearance. Kitchens with nearly nothing in them, speak of being above such common needs as cooking and eating. Minimalism is what people strive for, it is an aspirational aesthetic and brand. In the Eye on Design article Elizabeth Critchlow critics this rejection of consumerism to be in itself a very privileged position,

“People can afford to be minimalist because they can afford to throw things away, but know that they can re-buy it should they need to again in the future. They have that financial stability. I was raised in a way that you don’t throw anything away because you might need it again in the future, and going out and buying it again isn’t an option.”

(Khandwala 2019). Critchlow series of zines Minimalism (see figure 1 and 2) are a customisable cluttered celebration of collecting in direct opposition to minimalisms doctrine of declutter and its untouchable mystic (Khandwala 2019). She layers found objects in particular plastic bags, receipts, tickets and stickers to create page spreads that are as overstimulating as consumption is to your average person who has not reached the supposed “clarity” and “peace” of selectivity. She also included with each zine a pack of unused ephemera and encourages her audience to add to the jumble of imagery (see figure 3) (Critchlow 2019). This interactive element makes Critchlows zines feel accessible. It emphasis her rejection of the classist and alienist elements of minimal design by allowing the audience to not just observe her work from a dignified distance but be a part of the end result.

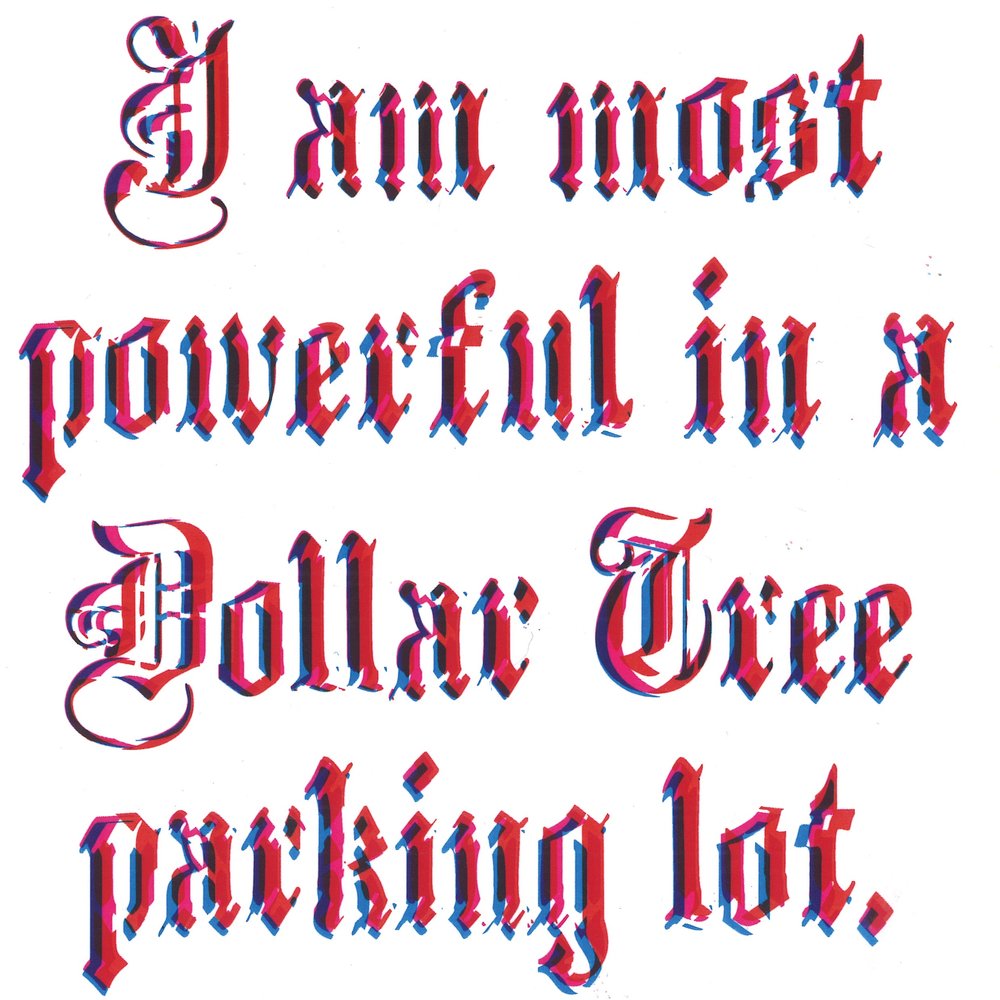

Another work of Critchlows stood out to me as I was browsing her website, Dollar Tree (see figure 4) a series of three typographic prints (Critchlow 2019). The prints read “I am most powerful in a Dollar Tree parking lot” in three different colour combinations (Critchlow 2019). The words speak of a lower class experience, standing outside a dollar store. This is a relatable experience to many people, they have been to dollars stores before, there is no luxury or exclusivity to speak of and yet she elevates the dollar store. She describes the experience as imbuing her with power (Critchlow 2019). What I connected with in this work is the type face itself. It is a Olde English style type, one which I would say falls under the umbrella of “bad taste”. It is tacky and cartoonish, and yet its historical connotation lend weight and religiosity to her words. The character of the typeface is what in turn imbues the content with power. Why do we consider it a poor taste typeface if it serves its function and adds to the design? I do not believe a simplified type that would be considered “fresh” and following modern notions of aesthetics would have had the same impact.

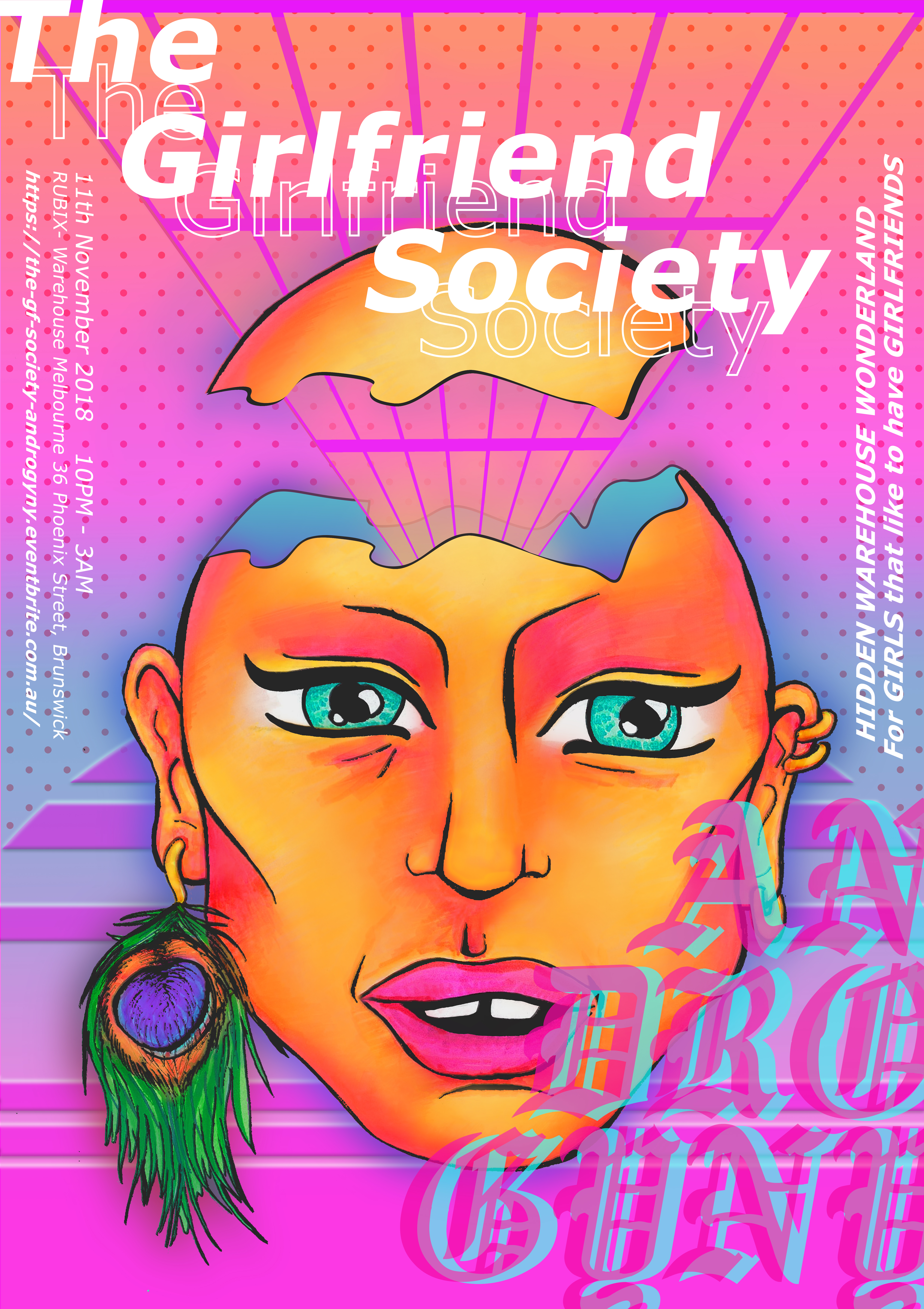

This type face appeals to me, I have even used it in a past work (see figure 5). In semester 1 of last year we were tasked to create an event poster, having spent a fair while attempting to create a clean modern looking design that was still visual intriguing I got frustrated. Out of this frustration I began to experiment with elements that I would traditionally consider “ugly”. The first of which was this type face. I thought it was so camp and jarringly 90s that using it would be funny. I showed some initial mock ups to my tutor who hated the type. They explained to me that there is a difference between poorly executed design and well executed design in poor taste. Rather than scrapping the type which had grown on me I changed the style of my design, focusing on creating a vaporwave inspired piece. Vaporwave which is a cyberpunk aesthetic that makes ironic use of Nostalgic 80/ 90s web design, neo classical elements, Japanese culture and cheesy internet humour (Bacon 2018). Its layered bold approach seemed such a relief to the stark rigid forms of minimalist design. It allowed me the freedom to have fun with colours and design motifs that would generally be considered in poor taste. I used gradients that I would have once deemed “childish” in design, hot pinks and purples that I traditionally would have thought of as garish. Why is it that I have these associates, these taste? Is it my personal view that I was born with? It seems more likely a taught standard because I liked what I made and yet I would never consider it a high piece of design. It wouldn’t be used by a up market brand or to promote an important event. Due to its maximised approach it has been taught to me to be seen as lower class, reserved for those who can’t afford the high price tag that comes with simplicity.

It is difficult to try see beyond class norms and standards in design but it is also critical. In order to create design that is ethical and new we must question our prior education and our perceived tastes. Push past the accepted idea of what is “good” taste and “good” design. Only when we each apply this mindset to our own design practise can we push design forward.

References

Redmond Bacon. 2018. The Vaporwave Aesthetic. Sound on Time. October 14. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://soundontime.com/vaporwave-aesthetic/.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bourke, Sarah. 2018. The Girlfriend Society. Copic marker, coloured pencil and digital manipulation.

Christoforidou, Despina & Elin Olander & Anders Warell. 2012. Good Taste vs. Good Design: A Tug of War in the Light of Bling. The Design Journal 15, no. 2.

Karyn Cooper. 2018. What is Minimalist Design?. Hunker. March 22. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.hunker.com/13709024/what-is-minimalist-design.

Penny Craswell, blog. 2018. Design and Maximalism: the Anti-Minimalist Movement. The Design Writter. September 4. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://thedesignwriter.com.au/design-and-maximalism/

Critchlow, Elizabeth. Dollar Tree. Digital print. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.elizabethcritchlow.com/dollar-tree.

Critchlow, Elizabeth. Minimalism. Zine series. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.elizabethcritchlow.com/minimalism.

Fagan, Chelsea. 2017. Minimalism: another boring product wealthy people can buy. The Guardian. March 4. 2017. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/mar/04/minimalism-conspicuous-consumption-class.

Ferry, Kathryn. 2017. Clutter and the Clash of Middle-class Tastes in the Domestic Interior. De Gruyter. September 5. 2017. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://www.degruyter.com/downloadpdf/j/culture.2017.1.issue-1/culture-2017-0011/culture-2017-0011.pdf.

Friedlander, David. 2016. Minimalism: Class, Fetishes and the Fate of the Planet. The Medium. September 2. 2016. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://medium.com/hothouse/minimalism-class-fetishes-and-the-fate-of-the-planet-7324255746e5.

Khandwala, Anoushka. 2019. Why minimalism is a class issue + You might not need that expensive adobe subscription. Eye on Design, April 3. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/why-minimalism-is-a-class-issue-you-might-not-need-that-expensive-adobe-subscription/.

Ada Ivanoff. 2014. What is Minimalism. Sitepoint. June 6. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://www.sitepoint.com/what-is-minimalism/

Jamieson, Ruth. 2017. In the world of magazines, what’s so good about bad taste? Eye on Design, January 12. Accessed April 15, 2019.https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/in-the-world-of-magazines-whats-so-good-about-bad-taste/.

Jenkins, Tiffany. 2014. Why we should stand up for good taste. The BBC. October 21. 2014. Accessed April 14, 2019. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140605-what-makes-good-taste.

Mack, Adam. 2012. The Politics of Good Taste. The Senses and Society 7, no. 1. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589312X13173255802166.

The Minimalist. Design Minimalism: What, Why & How. Accessed April 15, 2019.https://www.theminimalists.com/minimalism/

Marc Schenker, blog. 2018. The Minimalist Design Trend: Why Less is More. Creative Market. January 30. Accessed April 13, 2019 https://creativemarket.com/blog/minimalist-design-trend.