Everyone has different views and opinions that are informed by a multitude of factors including our education, up-bringing and morals. So it’s hardly surprising that we don’t all share the same view of what we consider as ‘beauty’.

Earlier this year, Zara, a Spanish fast fashion retailer released a campaign featuring Chinese model Li Jingwen which sparked outrage on Chinese social media. Many people were irritated at the campaign and vented on social media about it under the hashtag “Insult to China.” (May, Mou 2019) According to the New York Times, one commenter wrote, “Why are freckled faces misconstrued as high fashion?”, while another wrote, “just the West’s beauty standards for Asians, very different from ours. For those women to be called the most beautiful in Asia feels like discrimination to the rest of us.”(May, Mou 2019) It’s clear that many people believed Zara were being culturally insensitive by trying to push Western beauty standards onto the Chinese community. However, Zara posted a response on PearVideo saying that the campaign was for “global markets” and “our headquarters in Spain picked the model, they might have a different beauty standard… And we didn’t photoshop the photos”. (Chenyu 2019) Although it seems Zara never intended any harm with their photoshoot, it’s interesting to see how a seemingly small design decision created such an uproar.

The image itself depicts the home screen of a Zara webpage advertising their beauty products. On the left is their usual set-up of the shopping categories as well as their logo. On the right two thirds is a close up portrait of Jing Wen. Her face is angled to the right and her expression is quite monotone, with her eyes gazing towards the camera. The background is empty, her hair has been slicked back from her face and her clothing is black which ensures that the viewers eyes are drawn to her face, in particular the dark pink lipstick that they are advertising and also -perhaps unintentionally- her freckles. As her freckles are so visible, it gives the campaign a ‘natural’, unedited and fresh feel. Situated on top of her cheek are the large words “Beauty is here”, accompanied by some smaller type that reads “paint it matte, shine bright, ultimate, perfume”, making it obvious that the photo is an accompaniment to their advertising of beauty products. (fig.1)

I found it very interesting to read about this campaign and people’s abhorrence to it because to me personally, if I saw this on the Zara website, my only thoughts would be that it’s cool that there is Asian representation. To me, her freckles aren’t ugly, and she simply looks fresh faced and digitally unaltered. However, this just further proves how different people’s standards of beauty are because for so many people in the Chinese community, the freckles are hideous. As someone who is Australian born Chinese, it makes me wonder how differently my perceptions of beauty would be had I not been born in regional Australia.

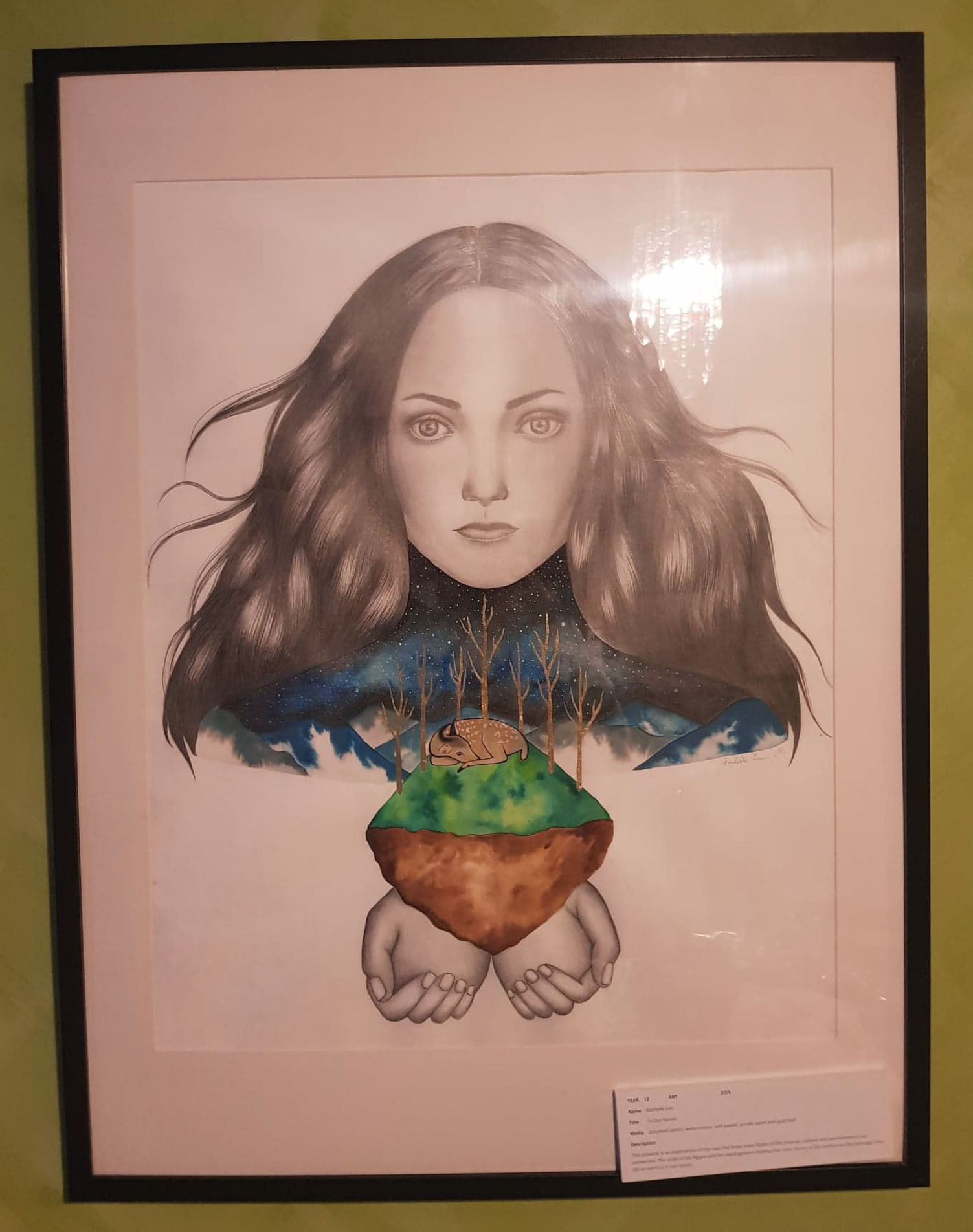

Growing up on the Mornington Peninsula, I was surrounded by Caucasian people. Not only that, the media around me, from movies, to books to advertisements also lacked in cultural diversity. Consequently, growing up, I always thought that Caucasian people were the most attractive group of people. This is very evident in the fashion illustrations I used to do, where I would draw skinny, white women with large eyes and pointed noses and it never occurred to me to draw people from other races. For my Year 12 VCE final pieces for art, I created three portraits of women, that were all Caucasian. The former artwork (fig.2), was based off a photo of a friend, so I do think it made sense that she is fair-skinned, with long wavy hair and large eyes, however for the two other faces (fig.3), I actually used a few different references of models and made up faces. And as you can see, they all have Caucasian features.

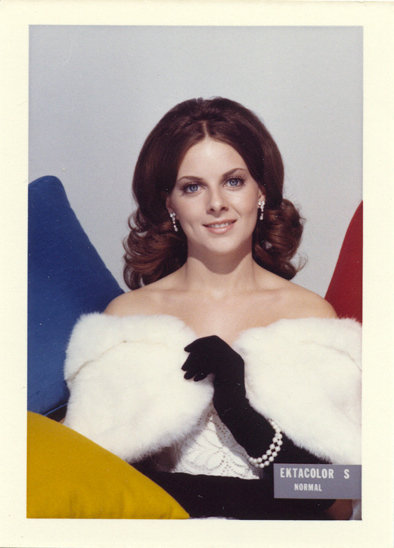

The way in which I unconsciously made these decisions aligns to the issues brought forward in Dimeji Onafuwa’s journal, “Allies and Decoloniality : A Review of the Intersectional Perspectives on Design, Politics, and Power Symposium” (Onafuwa, 2018) Onafuwa describes how the lack of awareness of designers can be discriminatory without them even realizing. (Onafuwa, 2018,). In the 1950s, there was an issue with the Kodak Shirley cards (fig.4) because for years, it was used by photo labs to calibrate skin tones, shadows and lighting during the printing process. (Del Barco, 2014) The film was flawed because it meant that if wasn’t suitable for people with darker skin and if a photo was taken featuring people with different skin tones, the shot would come out as partially under or over exposed. This goes to show how representing only one race is troublesome.

While it is clear that standards of beauty differ from person to person, it’s important to be culturally aware and encourage diversity so we don’t relive the same mistakes of the past.

References

Chenyu, Liang. “Chinese Netizens Decry, Then Defend, Zara Model’S Freckles”. Sixth Tone, Last modified 2019. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1003572/chinese-netizens-decry%2C-then-defend%2C-zara-models-freckles.

DEL BARCO, MANDALIT. “NPR Choice Page”. Npr.Org, Last modified 2019. https://www.npr.org/2014/11/13/363517842/for-decades-kodak-s-shirley-cards-set-photography-s-skin-tone-standard.

May, Tiffany, and Zoe Mou. “‘Insult To China’: A Model’S Freckles Spark An Online Storm”. Nytimes.Com, Last modified 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/world/asia/china-freckles-zara-jing-wen.html.

Onafuwa, Dimeji. “Allies And Decoloniality: A Review Of The Intersectional Perspectives On Design, Politics, And Power Symposium”. Design And Culture 10, no. 1 (2018): 7-15. doi:10.1080/17547075.2018.1430995.