The world of design and fine art have always been boxed together as a similar or singular discipline until recently. Design was almost seen as a branch of fine art and only started to gain a recognisable difference in identity and history in a modernist society. As a practicing designer and artist I have experienced both worlds separately and the relationship they both hold in the public forum as well as within the industries. The issues within design discourse have been explored by many practicing designers such as Frank Chimero. The power of knowledge could be the saving grace to solidify design in this age.

Design discourse has been an open ended question for a long time with many different opinions to further confuse it. Many ask what is it and what is seen as successful design? Is it interdisciplinary? 20th century modernist design like Bauhaus paved the way to creating a very heteronormative aesthetic in which we practice in our everyday life. Yet factors such as ethics, sustainability and the general responsibility design upholds is creating a new generation of design as we begin to have a broader understanding of how to contextualise our design practice in a post modern era. The concepts in which we are breaking down and analysing can propel a new attitude for design discourse so we can understand the future and fix these gaps and flaws that seem to plague the industry.

Victor Margolin1 described the differences of the art and design word, delving into the expectations they uphold socially and culturally. The art world has a structured formula or, “a framework for the presentation of a work ”2. It’s so well established with high status perspectives controlling the definition of art despite there being no ontological definition or, “definitive characterisation.”3 Whilst this art world system may have its flaws it has created a history and structure for the identity of fine art. On the other hand, there is an, “absence of a design world”4, which can be understood through the four spheres of design; research, education, discourse and practice. The research element has encountered an overhaul of information diluting the structure and understanding of design. The lack of outsider knowledge on design practice and its importance and place can not only discredit the industry but reduce, “financial and institutional aid”5 .

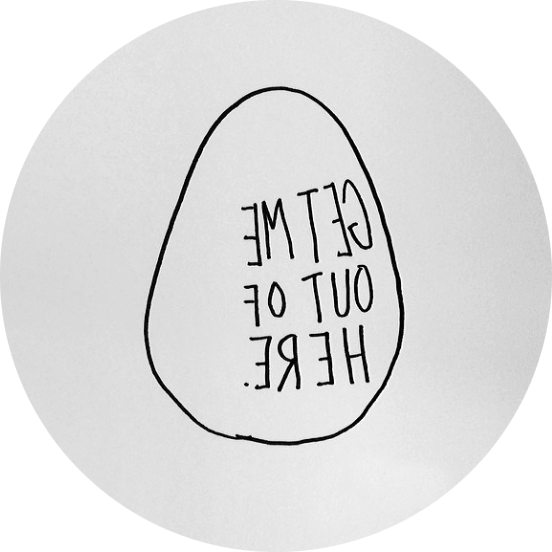

Frank Chimero is a designer, illustrator, and author working as a visual partner across branding, publication, and digital projects. As an active member of the design and art community he has written and spoken about many of the elements of design and how his practice has been influenced by the, “field’s principles and expectations”6. In a speech presented by Chimero at Harvard University for the School of Design, he breaks down design much like Margolin, but as design ideals; decoration, construction and articulation. Despite decoration being the first element of the viewers experience with the work, Chimero described the desperation and stress he felt to maintain a, “witty and likeable”7 persona throughout his work. Whilst the construction sector of Chimero’s design definition explained how he developed, “beyond appearances and begins to consider how work operates”8, yet it can subtract the ornamental aspect and implement a, “brute simplicity”9. The articulation of design is divulged as a combination of decoration and construction by “emphasizes clarity, fluency, and coherence over the maddening prettiness”10. The correlation between both Margolin and Chimero has introduced a new conversation between a new design world and the general public. I find strong relations between not only the theory but with the influence of process in my own practice.

Within my practice as an artist and a graphic designer I often find they impact each other yet are two very seperate practices. As an artist I create oil paintings often focusing on the human body and the relationship between the body, emotion and prevalent issues among young people. As a designer I have a holistic approach when working with companies as I believe it strengths my knowledge of how to create effective designs for the given context. I enjoy the idea of the design world and the fine art world interacting with the different practices and methods. Within my own practice I try to combine functionality with aesthetics and knowledge, as well as implementing ideas of social function and evoked emotion into both aspects of design and art. I believe that the influence of the two is strengthening my work by expanding the issues I base my ideas on from a personal sense whilst escaping, as Chimero stated, “the monotony of the media cycle”11 and towards more universal concepts.

As a university student you are introduced to the world of design and the baggage that comes with it. If you don’t manage to grasp the concept of the flaws and benefits of the field, you will begin to as you move into the workforce and experience them first hand. But during these first years, information is fed with a heavy focus on art history due to its more structural framework compared to that of design. Yet if students are encouraged to discuss design discourse and to question the, “mould for a designer”12, it will be influential in making additions to the current position and changing the way design operates in society. My understanding of design discourse has become more of a prevalent issue not only conceptually but in the physical world which is why I resonate with Chimero. Whilst I admire his works aesthetically and see similar colour schemes and themes between our works, his mindset throughout the process is how I contextualise my work with his. Growing from a young child who appreciates the aesthetic values, all the way through to ones career and beginning to move towards seeing that the, “conception of work is more flexible than we typically believe”13. Questioning that the mould a designer has to fit into, “does not suggest the mould is wrong, just that we may need more than one kind”14. This concept is evident in my perspective and is transferred into my process much like Chimero. As Margolin stated, “the chaos that currently exists in the design…this will not happen overnight”15, yet it remains a major influence in my practice, Chimero’s and hopefully many others.

Design discourse has remained a question mark for a long time and it will take significant effort from the industry and more appreciation and support from the external world to flourish. The expectations of a designer can be quite limiting in theory but there are a multitude of ways one can go about pursuing their design practice. As a fine artist and a designer I appreciate the correlation between the two and have a vested interest in seeing how they can strengthen each other in functionality and aesthetics. I find interesting correlations between my work and Frank Chimero’s, not only in the finished product but the process of our practice.

- Victor Margolin (2013) Design Studies: Tasks and Challenges, The Design Journal, 16:4, 400-407

2. Victor Margolin (2013) Design Studies: Tasks and Challenges, The Design Journal, 16:4, 401

3. Ibid. , 402

4. Ibid. , 404

5. Ibid. , 404

6. Frank Chimero, Harvard Speech adaptation (2014) History Design Studio Graduate School of Design, “Designing in the Border Lands”, accessed 2 April 2019, https://frankchimero.com/writing/designing-in-the-borderlands/

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Victor Margolin (2013) Design Studies: Tasks and Challenges, The Design Journal, 16:4, 406

16. Frank Chimero, Harvard Speech adaptation (2014) History Design Studio Graduate School of Design, “Designing in the Border Lands”, accessed 2 April 2019, https://frankchimero.com/writing/designing-in-the-borderlands/

Figure 1; Frank Chimero Graphics, accessed 2 April 2019, https://frankchimero.com/writing/designing-in-the-borderlands/

Figure 2; Frank Chimero Graphics, accessed 2 April 2019, https://frankchimero.com/writing/designing-in-the-borderlands/