I will explore how indigenous concepts of knowledge are at odds with traditional academic modes of acquiring knowledge through research, and how that nexus of ideas have been explored in three-fold as part of the Shapes of Knowledge exhibit at MUMA.

This is not an all encompassing analysis of indigenous design or rights, I am under qualified to give that.

Exploring the gap of knowledge production through the lens of Brian Martin, analysis of the meaning of the event

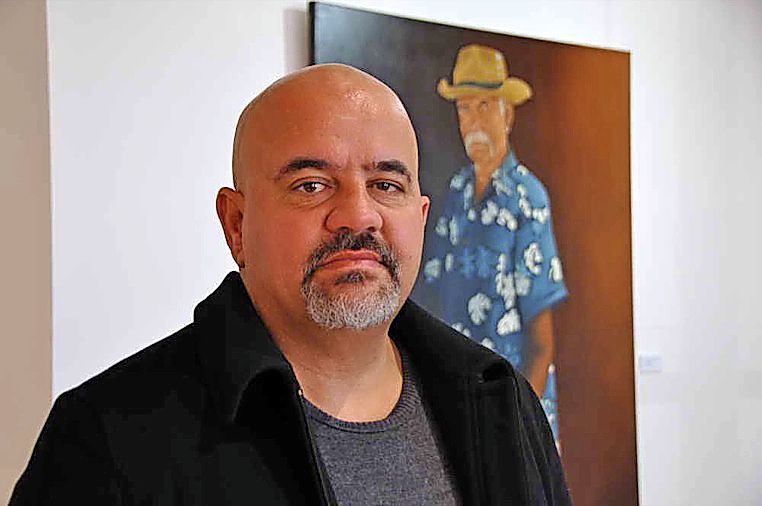

Dr. Brian Martin, a professor at Monash, is a descendant of the Muruwari, Bundjalung and Kamilaroi peoples and former deputy director of the Institute of Koorie Education at Deakin (1). He specializes in indigenous relations, and how they have been improperly engaged with for hundreds of years in Australia. He was thus a valuable speaker at Threefold, a series of three public talks on different ways of exploring knowledge and identity. These talks were an interactive extension of the Shapes of Knowledge exhibit (2) run by Dr. James Oliver, which explored how different entities produce and share knowledge. This particular event featured many speakers that presented on their particular corner of oppression in the world at large, and how universities are woefully unable to engage with it. The talks were pithy, engaging, and intellectually rigorous responses to the key question ‘Where is the university?’(3).

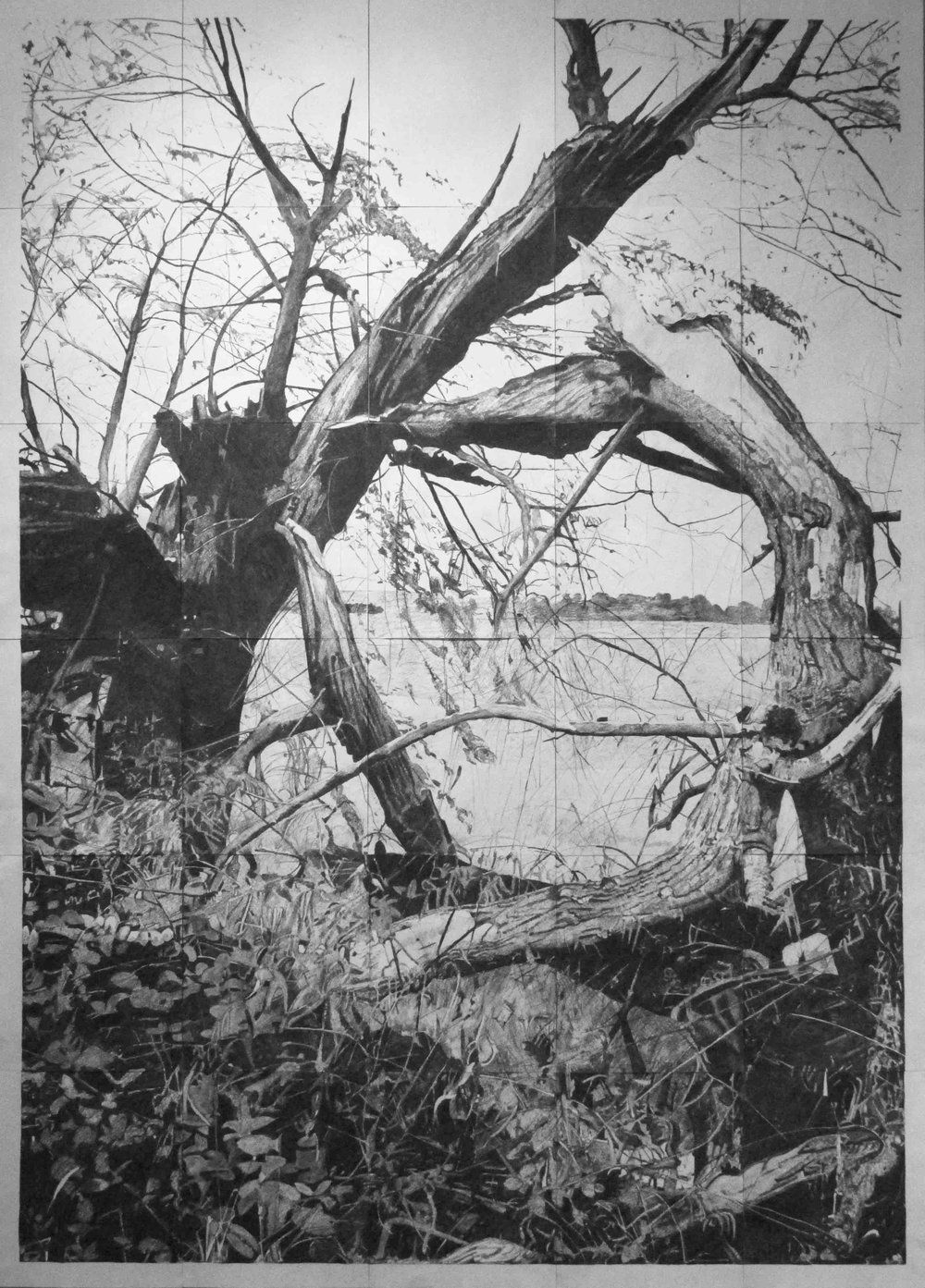

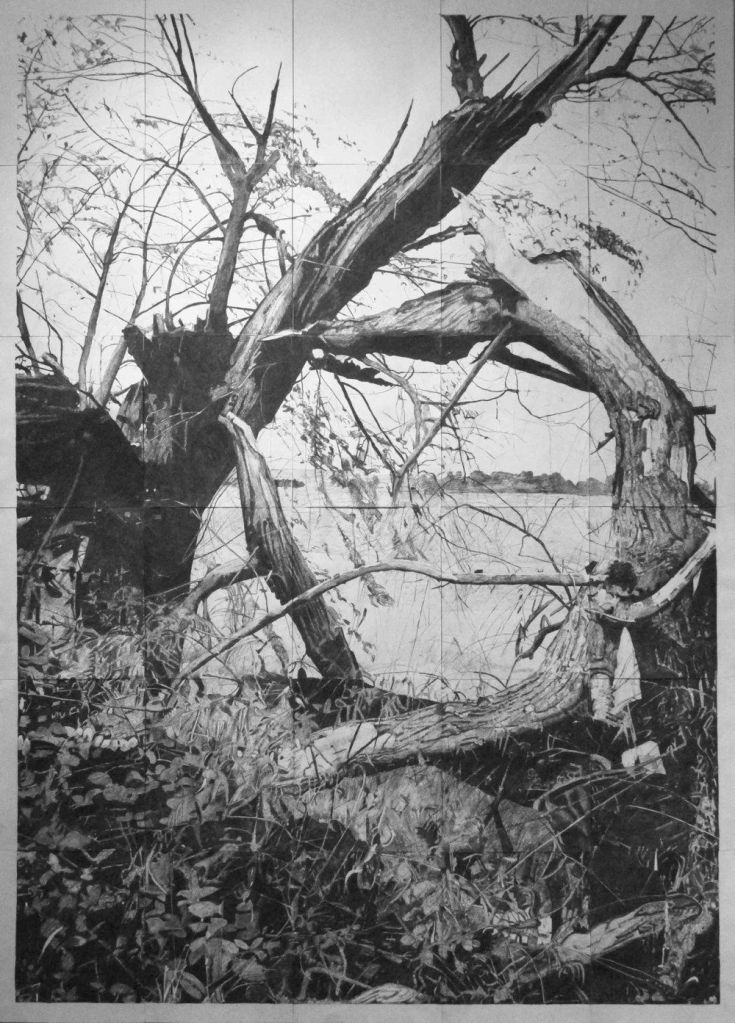

Most of the speakers gave a ten-minute performance. Martin, in contrast, did only two things. First, he played a video of his work, which featured him laying out single panels one by one to create a photorealistic charcoal sketch entitled Methexical Countryscape Kamilaroi #9. The work was simple, elegant and impactful, harnessing the full scale of artistic endeavour for political impact and sociopolitical engagement. This demonstration had no music or other distractions, which magnified the clear message that the ancient construction, and more recently, systematic destruction, of the natural environment had critically changed Australia and the relationship people have with country. Second, he quietly said one sentence: ‘The university is an abstraction from the land’.

Prof. Brian Martin

‘The university is an abstraction from the land.

During a later discussion, Martin broke down what he meant by this statement. The university is a physical distortion of the land that it resides on. Indeed, in order for the university to exist, destruction of place necessarily occurred. And with each extra story of each new building, the physical distance between the earth and dirt the land began as, is increased. Furthermore, the way university systems operate acts to mask the value of traditional indigenous knowledge production. The bureaucracies act as the foundation for the traditional model of tertiary education, value analysis, and vicarious inquiry rather than lived experience.

John Berger in his book ways of seeing explores the varying ways we can perceive and synthesize knowledge. Our perception of objects and our subsequent analysis of the significance of an object differ wildly depending on who is viewing it and the context they are coming from when they engage with it. This can be used to explore the alternative perceptions of land that exist between contemporary Australian culture and historical indigenous understanding. On the one hand, land is seen as financially valuable and as an object of power and control. This perception may be driven by a colonial conquest that is core to Australia’s history. On the other, there is a respect and interdependency of the indigenous community and land that has existed for an order of magnitude longer than a western capitalist viewpoint. This plays into the idea that “the relationship of what we see and what we know is never settled” (4) because these different narratives struggle to adequately engage with each other.

Universities remain bastions of the intellectual class and attempt to integrate their expertise and wealth of knowledge into society’s perception of success. As intellectual capital has been increasingly valued by society, perversely, societies own biases have reflected into university culture. Historically, universities have not been particularly culturally diverse, and when diverse or minority academics have been successful, they have done so in spite of an educational paradigm that did not value lived experience as a unique and worthwhile form of knowledge production. Establishment tertiary education has also transitioned more to integrating with industry and capitalist ideals. Entrepreneurship, graduate employment prospects, and tangible outcomes are increasingly the metrics of success through university. This commodification of intellectual output was laid out by Noam Chomsky in his 1967 essay ‘Responsibility of Intellectuals’(5) where he argues that intellectuals are increasingly becoming subservient to power rather than shaping power structures in society (). This, he argues, coincides with the decline of conventional consumerist western consumption and is a signal of late-stage capitalism.

Given that the alternative narratives between indigenous and western concepts of information, knowledge, and place are often incompatible, bureaucracies in institutions are sometimes implicitly prioritizing certain rights. A pushback against this is the indigenous design charter (6), that asserts that indigenous respect and engagement also extends to control over built environments, goods, and outputs. We see this in projects like the Mulka Project (7). Core to the successful implementation of such a charter is the concept of preemptive engagement. That is, rather than seeking consent for actions or decisions taken, like creating a new program or product, in order to be truly culturally sensitive those in power need to allow the indigenous experience to shape their decision making and task prioritization. It is not a final hurdle, but rather a first step.

Drawing upon Indigenous ways of knowing and political philosophy in the 21st century offers a critical lens to view the widening gulf between reality and the abstract ivory towers of the university.

References:

1. starweekly.com.au/news/referendum-exhibition-comes-to-werribee/

2. monash.edu/muma/exhibitions/exhibition-archive/2019/Shapes-of-knowledge

3. monash.edu/muma/events/2019/threefoldparallelperformance

4. waysofseeingwaysofseeing.com/ways-of-seeing-john-berger-5.7.pdf

5. nybooks.com/articles/1967/02/23/a-special-supplement-the-responsibility-of-intelle/

6. design.org.au/documents/item/216

7. monash.edu/muma/exhibitions/exhibition-archive/2019/Shapes-of-knowledge/the-mulka-project