Charlotte Perriand was a furniture designer and a voice for female artists shaping modern living in the 20th century. Born in 1903 in Paris, France, Perriand’s particular style was rebellious, as she insisted on moving towards machine-age technology rather than following traditions (Catherine Anderson, 2016). In the 1930’s, the furniture designer and architect was asked to increase the flow of Japanese products to the West, whilst also challenging the current styles among Japanese artists, designers, and architects. Through this research, Perriand designed the ‘522 Tokyo Chaise Lounge’ in 1940, made from a solid wood frame of bamboo sourced from Japan (see Figure 1). The seat is composed into twelve wooden curves, with the strips and bars joined by satin brass studs. This idea replaced the traditional method of steel-tubing that the Western designers were still using to construct furniture and appliances (Cassina Page, 2014). She turned the traditional bamboo processing technique into a modern piece of furniture, whilst also using and respecting the natural materials to their full extent. Perriand’s design was remarkably modern that you could easily assume it was produced on a larger scale just a few years ago.

The Tokyo Chaise Lounge aims to challenge the way designers used new materials, and making sure it was in a respectful and creditable manner to their source, whilst also creating a positive response – rather than critical – towards its origin. Prior to outsourcing the bamboo from Japan, Perriand researched the design culture over the span of five years, and spent her time exploring the possible uses that a versatile material like bamboo could have (Catherine Anderson, 2016). Subtly, she acknowledged its origin by naming the furniture ‘Tokyo’ Chaise Lounge, which creates a connection between the product and the culture for new consumers. Perriand also hoped the design of the 522 Tokyo Chaise Lounge would ignite conversations throughout the Western society, primarily about the possibilities and benefits of sourcing materials from around the world with the hopes of improving design in society.

Perriand was also particularly aware of the suffering in the world during the 1950’s, and knew that design could play a vital role in the discovery of solutions to create a fair society. The Chaise Lounge design is a great example of this, as Perriand did not rely on the cultural stereotypes from Japan to showcase or sell her design to the public. In relation to the Week 4 class discussion of design culture, Perriand could have easily used the Japanese art, food, or even the popular Kawaii style to influence her art and make it easier to understand to the white Western culture (Dimeji Onafuwa, 2018). However, she mindfully focused on the bamboo being environmentally friendly, undervalued and its popularity across the locals. If the design had been in the hands of a different designer, we could argue that exporting traditional resources to the Western culture could have potentially exploited how special and versatile it is, due to the substantial difference in cultures and the growing consumer demand happening in America at the time.

Perriand was confident in her skill of combining traditional and modern, which can be proven through the positive response of her furniture designs. However, an issue that arose was the functionality of the 522 Tokyo Chaise Lounge. Aside from its beauty and thorough design, people in Japan believed it may not suitable for mass production internationally, despite its practical use as outdoor furniture (Catherine Anderson, 2016). The Week 1 reading, Design Studies: Tasks and Challenges, discusses the idea that art and design are two separate entities, and they should follow a different set of rules (Victor Margolin, 2013). Artworks no matter what form they take, are not expected to produce a result or be a certain form, yet in design an expected outcome should be achieved. Perriand was a furniture designer, but did not necessarily focus on the mass production opportunities or how affordable she could make it. It was special, influenced by her travels and carefully thought out. The problem here is that both art and design were crossing paths in Perriand’s design, even though Margolin states that design should always have a purpose, a reason, and a problem to solve. The design culture in the 1950’s saw products having a higher turnover and a demand for more, which explains the one problem towards the availability of Perriand’s Chaise Lounge.

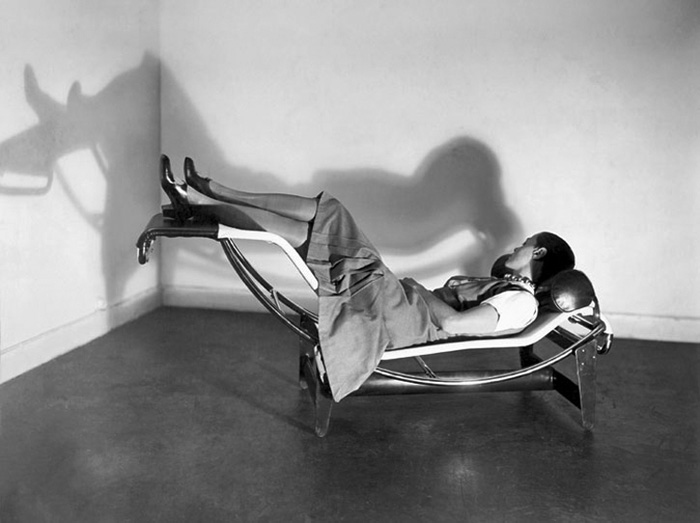

Besides the design, the advertising for the 522 Tokyo Chaise Lounge was heavily aimed at the feminine women and her physical appeal (see Figure 2). The idea was to photograph Perriand herself and other women draped across the lounge, with the intention of communicating modernity and femininity to the public. It could also be argued that sexualised women were used during the advertising to sell the product to the public. Perriand was unaware of the reaction her design may cause in the public eye from using a new outsourced material, so the idea to promote the product through the female gaze may have been a possibility.

One issue that is identified in Perriand’s work throughout her career is that they were not so heavily credited for. When she collaborated with Le Corbusier, he was often given sole credit for the conception and designs for the Chaise Lounges (Catherine Anderson, 2016). However, Perriand acknowledged that he had defined the framework of the overall forms of the chairs, but she had initiated the details, construction, and actual design. This issue can be related back to the discussion in Week 2, where Australian Indigenous design and cultural identity was explored. Commonly, the authorisation of artworks not being recognised can cause consumers to only remember the object but disregard the designers behind it. The entire meaning of the artwork can also be changed when it is not identified to its rightful owner (Dimeji Onafuwa, 2018). The risk of not acknowledging the appropriate artist is that it adds to the assumption that men in a white Western culture have created iconic designs throughout history, whilst proving the bias towards the women.

Perriand and her furniture design has pushed the idea of combining traditional with modern successfully, proving there is a way to promote new ideas without exploiting cultures and stereotypes. The issues that arose throughout her designs did not come from Perriand’s lack of research, but from a close-minded Western culture who may have not understood Perriand’s modernist style. She was always known to other designers for her research into the future, accepting change, and knowing when to experiment and when to just be respectful.

References

Figure 1. Charlotte Perriand, 522 Tokyo Chaise Lounge, Space Lounge, Cassina. https://www.spacefurniture.com.au/522-tokyo-chaise-longue.html

Figure 2. Charlotte Perriand, B306 Chaise Lounge, Renzoe Box. https://www.renzoebox.com/renzoeblog/charlotte-perriand

Catherine Anderson, Charlotte Perriand, Encyclopedia Britannica, 4th January 2016. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charlotte-Perriand

I Maestri, Charlotte Perriand, Cassina, 2014. https://www.cassina.com/en/designer/charlotte-perriand

Virtual Culture, The Structure of a Japanese House, Kids Web Japan. https://web-japan.org/kidsweb/virtual/house/house01.html

Onafuwa, Dimeji. 2018. Allies and Decoloniality: A Review of the Intersectional Perspectives on Design, Politics, and Power Symposium, design and culture, (2018), 10-11.

Margolin, Victor. 2013. Design Studies: Tasks and Challenges, The Design Journal, (Bloomsbury Publishing PLC 2013), 400-407.