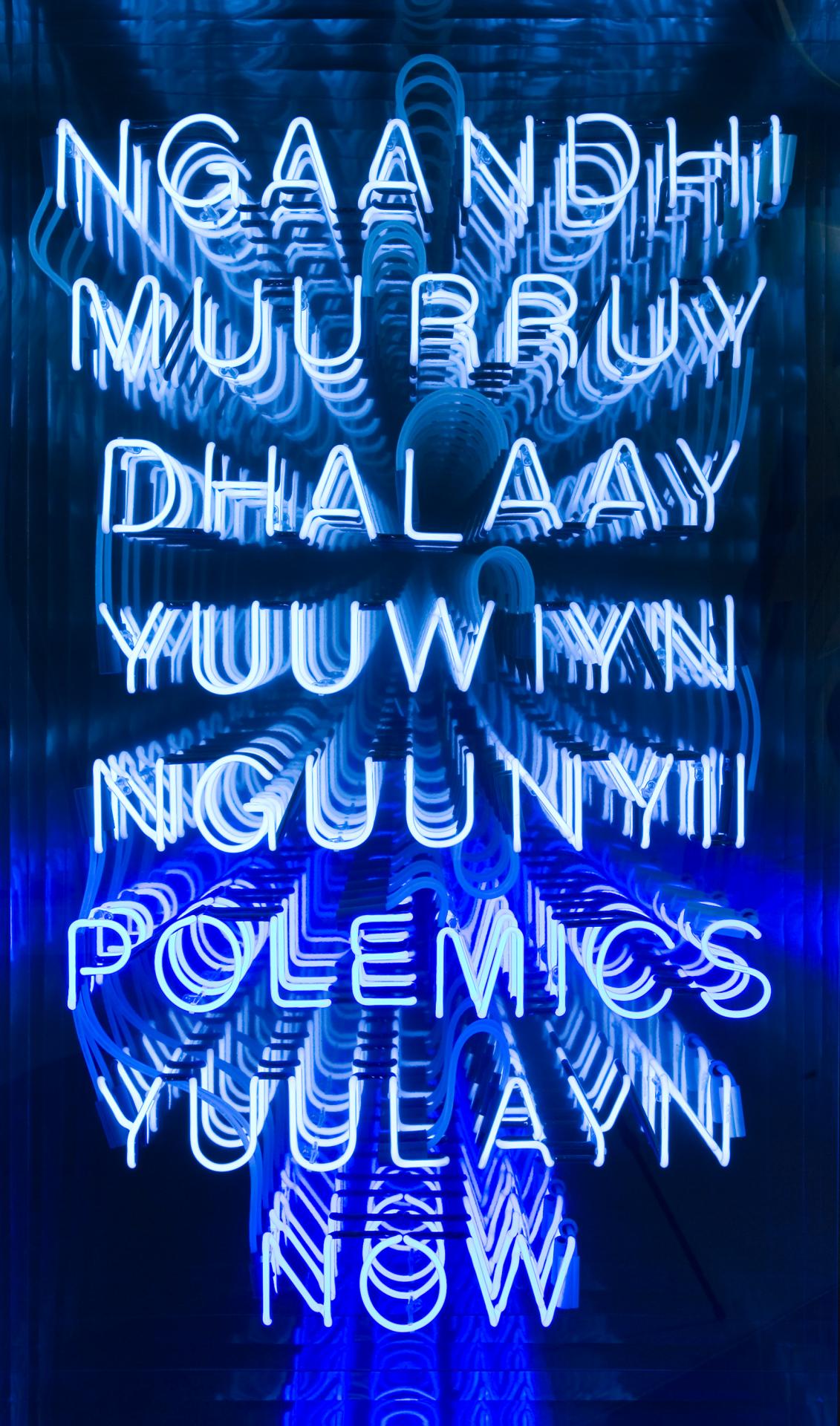

From Bark to Neon: Indigenous Art from the NGV Collection is an exhibition running from 3 November 2018 to 14 July 2019 and seeks to display the evolution of Indigenous Art in Australia. It presents artists from all over Australia, coming from different backgrounds, from individuals working in Aboriginal art centres to art school graduates working independently (NGV 2018). Like the title of the exhibition states, it shows the evolution of artworks from traditional forms such as cave paintings to a more modern interpretation through the use of neon lights, as shown in Brook Andrew’s Polemic (Figure 1), which utilises neon and mirrors to convey his ideas. This exhibition’s intentions align with those of the Australian Indigenous Design Charter (AIDC), where they seek to promote the representation and commission of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture through design (AIDC 2016) Where artists wish to convey their experiences through their artwork, the AIDC wishes that more designers would promote ethical use of these experiences in their design work, while still capturing the raw essence.

Before looking into the displays, walking around the exhibition there is definitely a sense of theming in the layout of the rooms. From the outside, the exhibition appears to be lively and joyful, with light coloured walls and brightly lit rooms. However, that changes when you enter the exhibition, past the first wall hides a detour towards a darker room (Figure 2) with less light, darker walls and less vibrant artworks. This seeks to represent the darkness and suppression that was evident in the history of the indigenous population. The lighting that was used throughout the exhibition was effective in creating an ambience to the room and evoking emotions toward certain artworks that otherwise may seem normal. The path to take through the exhibition is entirely up to the audience, they can either start with the more joyful rooms then the darker rooms, or take a detour into the darker room and finish up with a smaller, lighter room. The course you wish to take will no doubt change your emotional standing at the end of the exhibition. The darker rooms also felt more cramped with less space to move around, where as the last section (Figure 3) is a light and airy space.

In the last section, there was a piece in particular that stood out, one of the first pieces to be seen coming out of the darker room, with your attention directed at its vibrancy. Figure 4 shows an artwork by Sally Gibori that represents her husband, Pat Gabori’s Country on Dulka Warngiid (Bentinck Island), Dibirdibi, and tells a story where a Rock Cod ancestor of the same name has been said to have carved up the South Wellesley Islands using its fins and ultimately ending up on Sweers Island where he was caught and eaten (QAGOMA 2016). This story, among a couple others, is important to note as it creates the basis of which most of her paintings are derived from. This artwork is constructed by using synthetic polymer paint on canvas and was made on Mornington Island, located in North Western Queensland in the Gulf of Carpentaria, in the same area in which the artwork is representing.

Looking closely at the artwork, the brush strokes on the canvas are mostly harsh , and where the colours change, there is a buildup of paint. This could be a result of extreme emotions by Sally when the painting was created, and can be represented by the hardships she may have experienced in her life. This is important in the recreation of experiences through art as it allows for the audience generate their own emotions toward the artwork.

In relation to the intentions of the AIDC, although the artwork may not directly impact the designs of others, It allows for the audience, who may well include designers, to take into account these experiences to be reflected in their design. In that case the procedure in the representation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture in their design practice is encouraged by the AIDC through ethical and sound principles. They have been conceived to be an agent of change and to help the indigenous reconciliation process in Australia, and to encourage cultural innovation through inclusiveness (AIDC 2016).

For both the artwork and for design practices, respect and recognition are key aspects to the success of works. It is important to try and understand the culture and experiences of Indigenous Australians, and to represent this in the most ethical and accurate way. In the same way that Sally Gabori and other artists represented in the exhibition has tried to communicate her experiences, we as designers must recognise these experiences and to try to keep the emotion as raw as possible and to not dilute their views with that of our own. The AIDC intends to be used as a best practice guide when interacting with the indigenous people and representing their culture and provides framework in which to adhere to when attempting to express indigenous culture and our national identity.

References

[1] National Galley of Victoria, “From Bark To Neon: Indigenous Art From The NGV Collection – Artwork Labels”

[2] Indigenous Design Charter, “Protocols for sharing Indigenous knowledge in communication design practice” p5-6

[3] Queensland Art Gallery, ANCESTRAL STORYS AND PERSONAL HISTORY OVERLAP IN SALLY GABORI’S ART. https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/ancestral-story-and-personal-history-overlap-in-sally-gaboris-art/ (Accessed 28 March 2019)

[4] Indigenous Design Charter, “Protocols for sharing Indigenous knowledge in communication design practice” p8-9